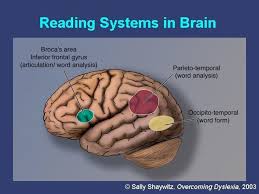

In order to understand how a child learns to read, one must understand how his brain works. In her book, Wolfe writes that the subskills required to read are learned in different parts of the brain. While these skills are developing, the brain must work harder and that trying to bring all those underdeveloped skills together too early can overload the brain. Also, the pace at which very young children learn to read is limited by biological timetables. Basically, rushing to get your child to learn how to read can cause issues for her down the line. Let her learn at a developmentally appropriate rate using developmentally appropriate tools.

There is no center in the brain that specializes in reading. In order to read, the brain uses many different neurological constructs from different sections. The back of the brain recognizes symbols. The temporal area (on the side) recognizes the sound. A third part processes the meaning of words. A different part of the brain process parts of speech. The frontal lobes allow for enough active working memory to remember, for example, the c sound as they move on to decode the rest of the word cat.

When neuroscientists take MRI scans of a brain that is just learning to read, many parts of the brain are heavily lit up. This represents how hard the brain is working. Once automaticity in reading sets in, the brain is not lit up as much- meaning it doesn’t have to work as hard. If the brain has one part of the reading process down, such as strong understanding of parts of speech, then more energy can be devoted to areas that are more challenging for that particular child. What you don’t want is for so many parts of a child’s brain to be working so hard at once, that the child gives up.

There are certain biological timetables for reading. One of the things that needs to happen before a child can read is the neurons must be myelinated. The environment cannot change the leraning timetable for this. However, even if a child biologically can’t read yet, there are many, many important things that need to be put in place so that reading, at the right time, will be ready to go.

The more we can learn how the brain functions while reading, the more efficient our teaching will be.

Reference

Wolf, M. (2008). Proust and the squid. New York: Harper Perennial.